- Home

- Austin Hackney

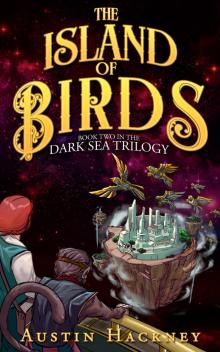

The Island of Birds Page 2

The Island of Birds Read online

Page 2

One gentleman carried a folding table which he erected in the middle of the Place. The other set the draped mechanical on the table and adjusted its position. Lifting one corner of the silk, he took a quick peek before letting the material fall back into place. Then he shrugged off his jacket and removed his top hat, handing them to his companion and exchanging both for a crank handle passed to him by the other man.

Still leaving the device covered, he inserted the crank in the side of the machine and gave it several vigorous turns. Clackety-clackety-clackety-clack, the ratchet stuttered through the air; the crowd now hushed, tense with anticipation. The gentleman removed the crank, handed it back to his companion, and turned toward the platform where Annabel sat. He bowed to the princess, and she acknowledged him with a graceful inclination of her head.

The cloth whipped away as the gentleman tossed it into the air. It swirled for a moment, a wisp of smoke, before gliding onto the warm sand.

“Your Highness,” said the gentleman. “My Lords, Ladies and Gentlemen; I present – the Phoenix!”

He flicked a switch on the side of the machine and stepped back. What a beautiful mechanical, Annabel thought. This gentleman is a master of his craft!

It was the size of a swan, but with the form of the mythical phoenix – the national symbol of the island. Crafted in colored metals, built from pressed plates patterned with intricate filigree feathers, and with embedded glass to allow the clockwork within to be seen, it was an exquisite piece of work.

For a few seconds, the automaton did nothing. But the sound of the spring unwinding and the rapid ticking of the creature’s clockwork heart built a sense of anticipation. Then the bird fluttered its wings, extending its neck, which swiveled and turned, bending downward to preen its iridescent mechanical feathers. It rose and spread its wings wide. Its tail fanned. A soft applause began, but the gentleman raised his hand and shook his head as if to say, Wait! Not yet!

The wings of the clockwork phoenix closed again. It folded its feathers and nestled its head onto its chest as if resting. After a heartbeat, flames exploded from beneath it, and fire engulfed the creature.

Flames flashed blue, green, orange and a devilish shade of red. Out of the fire, the phoenix arose. It spread its wings anew, fanning out feathers which sparkled with hundreds of glittering gems. Its neck stretched toward the sky. As it opened its bill, a haunting song tugged at Annabel’s heart.

With the flames dying beneath it, the mechanical bird lifted into the air and circled the Place of Assembly, swooping over the heads of the astonished crowd.

A volcanic applause erupted. The automaton returned to its original place where the mechanism unwound and it came to rest.

The display delighted Annabel. It was the best she’d ever seen by far – her own, good as it was, was going to be nothing by comparison. Her hands were red with clapping as the gentlemen gathered up their things, bowed and departed.

In the meantime liveried servants rewound the clockwork trumpet and inserted a new music roll. Once again it piped a marching tune as the parade got underway. Makers displayed mechanical after mechanical, either carried by their creators or flying overhead. The parade made its way around the perimeter of the Place of Assembly, each new creation eliciting a fresh gasp of wonder from the crowd, each surprise evoking applause, or laughter, or both.

A flock of tiny hummingbirds flashed over Annabel’s head. Iridescent starlings shimmered in a mechanical murmuration. A mechanical monkey danced on an ostrich’s back.

Annabel’s piece, a singing clockwork sparrow made to scale, received a generous applause despite its simplicity. It was a pretty thing, and she felt pleased with it, even as a pang of painful regret pulled at her heart. If only Dad could’ve been here. He loved the parade.

Annabel watched the event with a mix of childish delight and adult curiosity, her brain whirring as she tried to understand how the mechanisms worked.

But at last the Parade of the Bright Mechanicals came to an end. The judges selected the winners in first, second and third place. Annabel stood as each of the successful contestants stepped up to the throne, bowed or curtsied, and received their prizes from the hands of the princess.

Annabel was ready to sit again when the Regent towered at her side. He leaned in toward her and whispered in her ear. “It is time for you to declare war,” he said, extending his arm. His breath smelled of peppermints.

Annabel’s gut twisted. She refused his arm. Not much longer now, she thought. She scowled at Cranestoft. You’ll regret this when I’m queen!

The crowd was quiet again: the only sounds the occasional shuffling of feet or a stifled cough. Annabel walked by Cranestoft’s side as he led her from the platform and across the Place to the ceremonial entrance. Cool air chilled her as, accompanied by the inevitable armed guards, the Regent led her into the palace. They climbed a sweeping staircase, walked through the halls, into the Throne Room, and out onto the balcony.

A lectern, fashioned as a phoenix, awaited her. On the back of its wings, the unfurled scroll. Annabel hesitated. Cranestoft glowered. “Princess,” he said.

Annabel walked forward, resting her shaking hands on either side of the lectern. She leaned toward the brass amplification cone and read the Declaration of War.

Chapter Two

Davy’s swarthy head appeared above decks, his dark eyes serious as ever. “We’re closing in, Cap’n,” he said. “We should pull down.”

“Aye-aye,” said Harriet. “Decrease the pressure and loosen the rig. It’ll be a steep drop by the looks of it.”

A few moments later, the gas-release valves hissed. Steel rigging creaked and twanged. Harriet cut off the propellers. The ship made a sharp drop, sending her tummy into her rib cage. They dipped out of the Dark Sea into the blue skies of the island’s local atmosphere.

Harriet steadied the ship. She let the vessel drift while she scanned for a safe mooring site. Forest covered most of the island. Multicolored birds flickered through the green canopy. Wide, lazy rivers meandered through the forests, and emerged into broad floodplains, spilled onto water meadows. Blimey, it’s beautiful! thought Harriet. Even more than the legends say. Then she saw something that made her catch her breath.

“Sibelius,” she said. She nudged her friend in the ribs without taking her eye from the scope. “Is them what I think them is?”

Sibelius took the telescope and looked. “Zut alors! Mais, c’est incroyable! It is incredible. They are unicorns!”

In the flower meadow below, the delicate beasts grazed in a great herd, their spiraled horns flashing silver in the light of the island’s sun.

Harriet took the telescope back, but before she could look again, Davy came charging up the ladder, his eyes wild, panting. “Cap’n!” he said. “Cap’n! We’ve got trouble!”

“What kind o’ trouble?” Harriet said. “If we’ve no more fuel, I can float her onto one o’ them rivers, they’re wide enough.”

Davy shook his mop of black hair. “It’s not that,” he said. “Look!”

In the distance, at the center of the island, a shining city thrust skyward from the peak of a mountain. Ivory-white towers and golden cupolas of a scale and grandeur Harriet had only seen in books of fairy tales glittered at its heart. Mighty grand that is. Looks like the only city, too. I reckon the whole island’s not much bigger than Lundoon back on Earth.

But it wasn’t the palace which alarmed Davy, she realized. Between the city and her starship, five objects flew toward them. Fast. Giant birds? Monstrous, metallic eagles.

Harriet’s heart flipped. Her palms were clammy. She shot the telescope to her eye again and pulled it into focus “They’re mechanicals,” she said. “But they’re flying like birds, on big metal wings. I ain’t never seen the like.”

“You think, mademoiselle,” Sibelius said, “they have seen us?”

“I reck

on they’re heading straight for us,” she said. “And they got guns. It don’t look friendly.”

“What shall we do, Cap’n?” Davy said. “If they’re attacking, we’re done for. We’re unarmed.”

The mechanical birds were zooming closer. Couple o’ minutes and they’ll be on us, Harriet thought.

“We can’t fight ‘em,” she said. “Best thing is to head back into the Dark Sea, I reckon. Tighten the rig again Davy and get Barney to drop a quarter o’ the ballast.”

Davy nodded and ran to follow his orders. Harriet snatched up the communications tube, cranking the handle hard. “Sam! Fire her up again! And make it snappy!”

“But Cap’n, we ain’t got no fuel. We’ll never…”

“Use the reserve. Dump your rum in her engines if you have to, but fire her up!”

“Aye-aye, Cap’n!”

The cables twanged as they tightened; the engines thrummed beneath her feet. But it was too late.

Dark shadows blotted out the blue sky. Harriet’s ears pounded with the clattering of mechanical wings. Machine gun fire ripped the air. Rat-tat-tat-tat-tat! Harriet launched herself at Sibelius. The two thumped to the decks as a line of holes blistered the spot where he’d been standing. Rat-tat-tat-tat-tat! The inflatable exploded. The ship listed, throwing Harriet against the balustrade as a ball of fire billowed above her.

“Sibelius,” she gasped, “Everyone below decks! I don’t want no-one shot!” The mechanical aircraft swooped away, banking round for a return pass.

The prow tipped forward, the ship threatening to fall into a fatal spin. “I’ll try an’ stabilize her!” Harriet said, struggling towards the drive wheel. “Tell Sam to get them propellers full speed!”

Sibelius slid across the sloping deck, swinging from the ladders, shouting Harriet’s orders.

Harriet dragged herself to the controls. She knew what lay beyond the boundaries of the ship, and she didn’t want to see it: a blur of speed and danger as the vessel tumbled toward the forest. Blooming nice welcome to paradise, she thought, as she threw switches and pulled levers, leaning hard on the wheel to right the ship. If I can get her straight, I can land her in one o’ them rivers…

Every muscle straining to snapping point, Harriet forced the ship upright, yanked the accelerator lever and held it as far as it went, listening for the chop-chop-chop of propellers above the rushing air and rattling gunfire. That’s it! That’ll give us enough push to stay more or less upright. At least for a few seconds. They were hurtling closer to the forest.

Ratta-tat-tat-tat-tat! Bullets punctured the deck, showering her with splintered wood. That’s blooming close. The propellers sputtered and died. Frick! We’re out o’ fuel. She swore.

The starship was her pride and joy, her home: the beginning and end of everything she cared about. If she tried to land now, she’d risk the lives of her crew. If she gave the order to bail, she’d lose the ship for sure: the ship which had cost her blood, sweat and tears; her dream come true; her father’s last legacy. She cursed. Blast it! After all that.

The wheel tugged against her; levers rattled and jumped in their housings. The forest loomed, flashing so close she could see individual leaves. Oh beggar it!

Just before her muscles could snap like broken rigging, she slipped from the controls, letting the wheel fly. “Bail out!” she yelled, tumbling below decks. Her crew was grabbing bat-wing packs from the emergency rack. They clambered back out. The wheel rocked and then span, picking up speed. Another fraction of a second and it would be too late. “Bail out!”

Harriet pulled one of the stiff leather packs onto her back and tightened the straps. She turned the crank on the side of the pack as the clockwork mechanism wound tight. At the edge of the ship, she pulled her goggles over her eyes, climbed onto the balustrade with the others, leaned into the wind – and jumped.

For a few seconds she fell through the cold, blue emptiness; then, gritting her teeth, she yanked the rip cord. The bat-wings – oiled leather stretched over a wooden framework – sprang from the pack. Harriet flew, the mechanism clattering behind her back, as she regained control.

The crew had made it. It was impossible to speak through the ripping air, so she gave them the thumbs up and beckoned for them to follow her. As if I’ve the foggiest idea where I’m going.

The forest stretched on as far as she could see. No chance, Harriet. We’d be snagged and strangled. But she knew they’d have to land soon. The bat-wings were for emergencies only and would unwind quickly, leaving them to fall to their deaths.

The mechanical birds banked again, circling the starship as it crashed into the forest; wood splintered; twisted metal and snapped cables screeched through branches; the burnt-out leather inflatable ripped and snagged.

The salty sting of tears surprised Harriet. Now I can’t even see proper. She blinked the water from her eyes. Well, I lost me ship, but I’m hanged if I’ll lose me crew, to boot!

She caught sight of Sibelius. He waved his hairy arms wildly. What’s up?

Maneuvering mid-flight, she understood what he meant. They were flying close together as a crew. Like a crazy flock o’ dumb pigeons back home, she thought. Just asking to be blasted out o’ the sky! Sibelius was pushing his palms outwards. Realization dawned on her shipmates’ faces, too. Spread out! He was gesturing with increasing urgency. Spread out!

The punishing back-draft from their attacker’s craft buffeted her into a spin. Her muscles tensed, ready for the bullets that would bring her adventures to an end. But the bullets didn’t come. Rather than let rip another round of fire, the aircraft reformed and sped away, back toward the city. Maybe they didn’t see us bail, Harriet thought. Or maybe there weren’t nobody inside ‘em…

Her backpack’s mechanism faltered – clack, clack, clack – and stopped. Now we’re done for. The last thing she saw was Sibelius, whose bat-wings had also failed, laughing as he somersaulted to his death. And then she, too, fell out of the sky.

Chapter Three

Annabel stopped playing and slammed the lid of the clavichord shut. The bass strings thundered in resentment and her First Maid, Katy, almost jumped out of her skin.

“Annabel!” she said, shaking her head and settling chubby hands on ample hips. “Whatever are you thinking?”

Annabel slumped back onto her stool, feeling defeated. She sulked. It was childish, but she was annoyed and couldn’t help it. “I hate the clavichord!” she said. “There’s no reason I should learn to play the wretched instrument at all. Why do we need to go through this torture every afternoon? We have perfectly good mechanicals to play music, so why should I have to do it?”

“It is proper that a young lady should learn music and art and all the graces,” Katy said as if reciting from a catechism.

“Oh tosh! There isn’t even anyone who will listen to me play. Apart from you. And you don’t count.”

Katy pursed her lips. She lifted the lid of the clavichord. Then she turned a page of music. “Try this one,” she said.

Annabel looked at Katy but the maid wouldn’t meet her eye. Annabel felt ashamed. She had let her temper get the better of her again and the consequence this time was she’d hurt Katy’s feelings. Katy doesn’t deserve that, she thought. The maid always meant well, and she was kind and good. Katy lacked imagination, that was all. She’d been the closest thing to a mother Annabel had known.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I was rude. I didn’t mean it. Of course you count. You’re very dear to me, Katy.”

Katy blushed. “Well, never mind. Although I would expect better behavior from a young lady who will become the Queen. Besides, it isn’t only me who listens to you play. You understand perfectly well the Lord Regent keeps an ear open for you from his offices below. The sound carries. I had occasion once to go in there when they were installing this contraption.” She patted the instrument’s polished walnut sur

face. “I could hear every move they made.”

Annabel smirked. “You called the clavichord a contraption,” she said. “You don’t care for it either, do you?”

Katy smiled back and winked. “As you ask, I’ll tell you: not much! But that’s not the point. Now you’d best get some sound out of it or his lordship will be up here and we’ll both be in all kinds of trouble.”

Annabel lifted her hands, spreading her fingers to have another go at making sense of the annoying squiggles of black ink on the page in front of her, when an ornithopter clattered past the window. The back-draft sent the sheet music fluttering like feathers from a burst pillow.

“Oh botheration,” Katy exclaimed, rushing to gather up the scattered paper. Annabel pushed the stool away and dashed to the window.

“They’re back,” she said. “But I wonder what happened to the ship.”

“What ship?” Katy said, straightening up, red-faced. She patted the papers back into order on top of the clavichord.

“Surely you saw it? I told you about it. The alien flying machine. They sent ornithopters out to it. I didn’t get to see what happened. But they’ve come back, and the ship is gone as far as I can tell. I wish I had seen what happened! Why doesn’t anyone tell me anything?”

“The Regent will bang on that door in a moment if you don’t get back to your practice, Your Highness,” Katy said, rattled.

“If he doesn’t just blast it open with a gun,” Annabel said, returning to the stool and plonking herself in front of the despised instrument. She half-heartedly played out a few notes. Then an idea struck her. She looked at the grandfather clock in the corner. A quarter to three.

“How much more practice do I have to do?” she said, her voice quiet.

“Just until half past and then it will be time for you to retire for your afternoon nap.”

“Same as ever, then. And after a nap, a stroll in the gardens before further pointless activities such as needlework and dancing lessons. But no reason to see Lord Cranestoft again until dinner, is that right?”

Dragon Moon: Lia Stone: Demon Hunter - Episode One (Dragon-born Guardians Series Book 1)

Dragon Moon: Lia Stone: Demon Hunter - Episode One (Dragon-born Guardians Series Book 1) The Island of Birds

The Island of Birds Wolf Moon: Lia Stone: Demon Hunter - Episode Two (Dragon-born Guardians Series Book 2)

Wolf Moon: Lia Stone: Demon Hunter - Episode Two (Dragon-born Guardians Series Book 2)